|

> The Appraiser Coach

> OREP E&O |

Introduction to Business Valuation: Key Insights for Appraisers

by Seth Webber and Casey Karlsen, Business Valuation Resources

Moving from commercial real estate appraisal to business valuation set me up for a real shock. On my first day with the new firm, I was given a business valuation to familiarize myself with. My confusion began with a capitalization rate in excess of 20 percent. This was double or triple of what I was used to making from commercial real estate! My unease mounted when the market approach included dozens of transactions, rather than a tidy group of six or eight real estate comps. I began to question the credibility of my new firm and asked my old real estate boss to meet up to discuss. Over lunch, he helped me understand the differences between business valuation and real estate appraisal, which put my mind (and my career transition) at ease.

From that firm, I joined a prominent national firm for a couple of years before settling into the business valuation group of an accounting firm headquartered in Maine. All three firms followed consistent valuation practice, reinforcing the message that these “crazy” valuation capitalization rates and multiples were actually perfectly normal in business valuation.

Real estate appraisers could benefit from learning about the sister discipline of business valuation to avoid the shock factor upon one’s first exposure to business valuation. Clients of real estate appraisers may also have business valuation needs, and the ability of an appraiser to be of assistance in these matters as well may be beneficial.

Assets and Liabilities Included in a Business Valuation

One of my clients owns a long-term care facility here in Maine. The business has debt collateralized by real estate, and recently a real estate appraisal was performed. My client then decided to gift shares in her business to her son. When filing gift tax returns, my company’s policy is to request a business valuation to substantiate the return. The owner balked at spending more money for a valuation after just having a real estate appraisal. “Can’t we just use the value from the real estate appraisal for the gift tax return?” she asked.

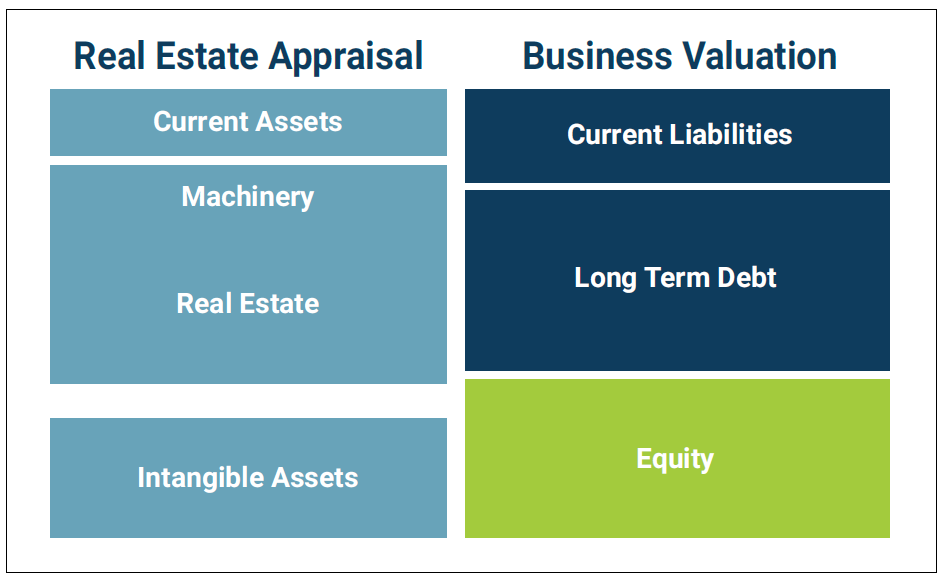

Balance Sheet of a Company

There are three primary problems with this. First, real estate appraisals may or may not capture the intangible value of a company—brand awareness, customer relationships, cultural elements, etc. Second, real estate appraisals rarely include all the assets owned by a business, such as vehicles, cash, equipment, and other assets. Lastly, business valuations for gift tax returns, as well as most other purposes, conclude on an equity value. That is, liabilities are subtracted from the asset value. (See Figure 1: Balance Sheet of a Company.)

Figure 1: Balance Sheet of a Company

Risk and Value

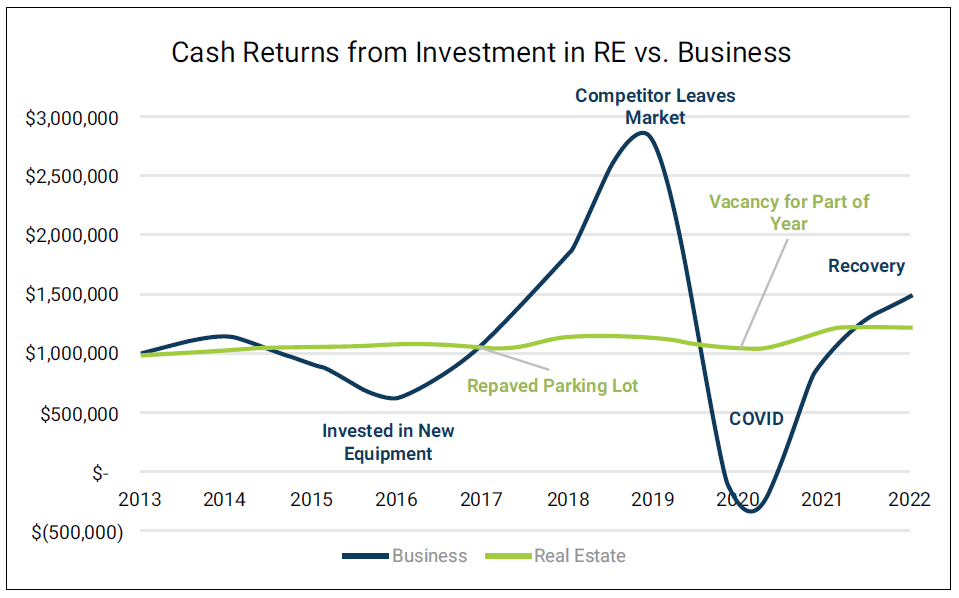

Business capitalization rates are often double or triple that of real estate capitalization rates. Much of this difference boils down to risk profiles. Operating businesses are a riskier investment than owning real estate. One in five businesses fail in their first year. By the end of five years, about half of all businesses close their doors. Even when they don’t fail, a business’s cash flow can be much more volatile than returns from a real estate investment, as shown in the accompanying chart. (See Figure 2: Risk and Value.)

Risk and value are like children on a teeter-totter. When risk goes up, value goes down. This risk is captured in business valuations through higher capitalization rates and lower multiples.

Drivers of Value (Sources of Risk)

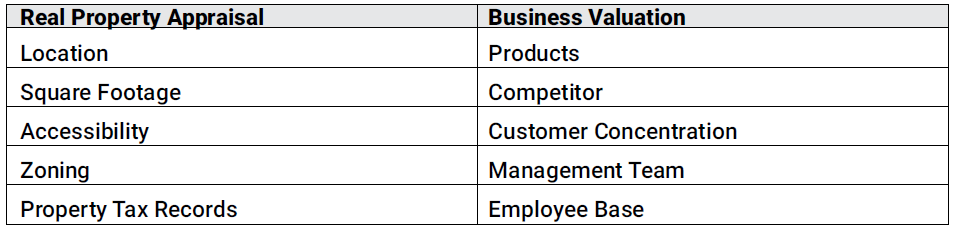

Business valuation analysts look at drivers of value different from real estate appraisers. A handful of key drivers are summarized in the chart. (See Figure 3: Drivers of Value.)

Financial Statement Analysis and Adjustments

Business valuation is fundamentally forward-looking. What happened in the past is irrelevant, except as it affects and establishes a company’s trajectory into the future. To that end, business valuations typically include a review of the last five years of financial performance as an indicator of where the company is headed.

Sometimes, unusual events put a crater in the financial trajectory. If this event is nonrecurring and won’t happen again in the company’s future, analysts may make an adjustment to smooth over this pothole and create a clearer picture of what the future might hold.

Other common adjustments include addbacks or deductions related to the owner’s compensation and rent expenses. The goal of these “discretionary” adjustments is to capture all costs and benefits of ownership within the income stream of the company.

(story continues below)

(story continues)

Nonoperating Assets

In my real estate career, I had the opportunity to value an extremely overbuilt RV park. It had hundreds of spaces, despite limited market demand. We decided the highest and best use was an RV park with less than 100 sites and vacant land to be developed in a different enterprise. In other words, we separated the operating assets from nonoperating (surplus) assets.

In business valuations, the same process is done. We look for assets unrelated to business operations (boats, condos, vehicles for family members, etc.) and add them to the business value as an additional source of wealth.

Market Approach

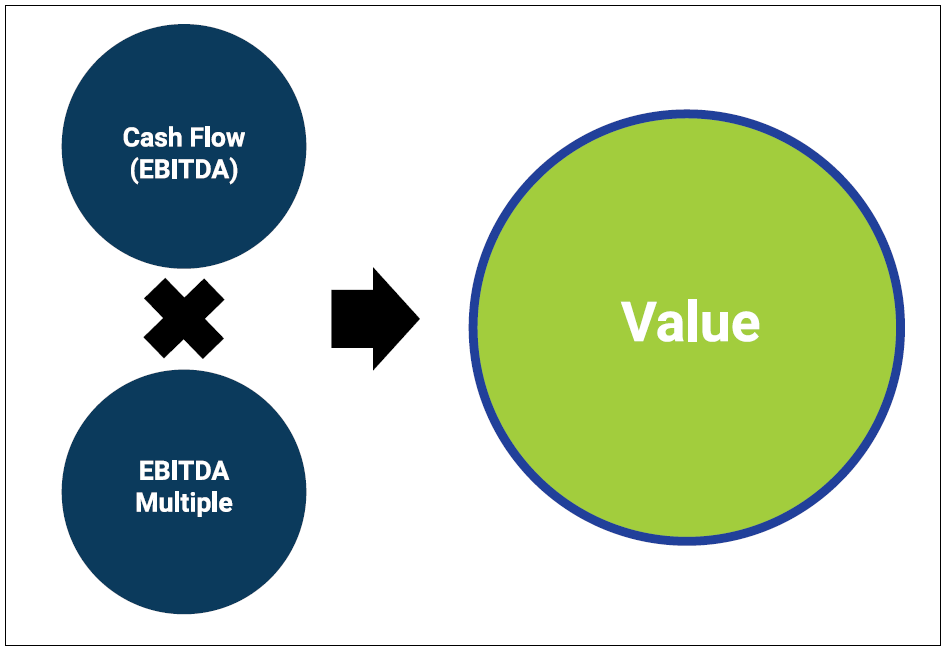

Business valuations use slightly different terminology, referring to the sales comparison approach as the market approach. Naming differences aside, the methodology used in business valuations and real estate appraisals is fairly similar. However, rather than focusing on price per square foot, business valuations use EBITDA multiples. (EBITDA, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, is a standardized measure of business profits.) Business value is calculated on Figure 4: Market Approach.

The first time I saw a business valuation report, I was surprised to see about 40 transactions used as comparable sales. Further, the EBITDA multiples from these transactions were all over the map, ranging from 2x to 15x. There appeared to be much less due diligence spent on each transaction than I was used to. Each of these observations has a reasonable explanation behind it.

- Number of transactions: When comps are highly similar to the subject, few comps are necessary to elicit a reliable indication of value. A larger group is necessary to create an accurate picture of marketplace pricing trends when comps are dissimilar. Unfortunately for business valuation analysts, differentiation is the name of the game for businesses.

- Wide range of valuation multiples: Valuation multiples also vary widely from transaction to transaction as they are highly sensitive to a company’s risk profile and the circumstances surrounding a deal.

- Limitations on due diligence: Buyers and sellers often prefer to divulge as little information about the transaction as possible. Often, the transaction summaries available in databases have the names redacted. This greatly impedes an analyst’s ability to do a deep dive into each transaction. Additionally, the number of transactions utilized makes this less feasible.

Income Approach

The sales comparison approach is often given primary weight in real estate appraisals, with secondary weight to the income approach. In business valuation, it has been my experience that the inverse is true: the income approach is often the valuation analyst’s bread and butter. The discounted cash flow (DCF) method, in particular, is the weapon of choice.

The reason for the popularity of the DCF method is its flexibility. The DCF method can accommodate anticipated fluctuations in cash flow and can be tailored to match the risk profile specific to the subject company.

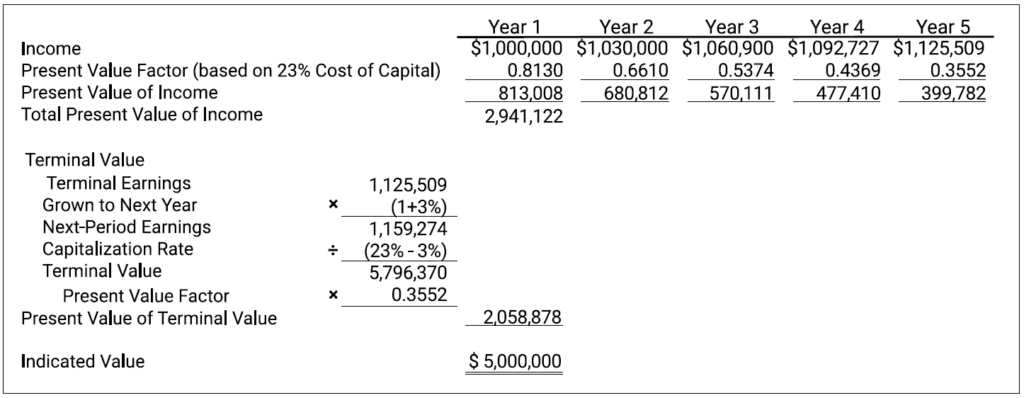

When applying the DCF method, analysts discount income from a discrete forecast period to present value. The length of the discrete forecast period should match the economics of the subject company, extending until growth stabilizes. Once growth stabilizes, income is capitalized in perpetuity using the Gordon Growth Model, and then discounted back to the valuation date. A simplified version of the DCF method is presented in Figure 5: Income Approach.

Asset Approach

The asset approach is quite similar to the cost approach in the appraisal of real estate. In the asset approach, analysts estimate the value of a business by valuing each individual component of the business that a hypothetical buyer would have to recreate. Analysts adjust each asset and liability on the balance sheet from book value to fair market value. Additionally, analysts value off-balance sheet, intangible, and contingent assets and liabilities. Unless a business has acquired another business, intangible assets are generally not listed on the balance sheet. The aggregate value of these adjusted assets is then reduced by the adjusted value of the liabilities, resulting in an indication of the fair market value of the equity of the subject company.

The asset approach is most useful for valuing asset-intensive companies (hotels, railroads, quarries, etc.). The income and operations of these companies are largely a function of their fixed asset holdings. Accordingly, their value is primarily driven by the assets that they hold. By valuing the fixed assets that these companies hold, an analyst is well on their way to estimating the value of the entire business.

The asset approach is less useful for service-based companies. The value of service-based companies has much less to do with their fixed assets. Consider an architecture firm. On its balance sheet, the architecture firm may have some desks, furnishings, and computer software, none of which have much value. Instead, value is driven by intangible assets not reported on the balance sheet, such as customer relationships.

Valuation Discounts

Ownership of businesses is often divided among several parties rather than just one person.

Valuation analysts are often retained to value a specific person’s interest (e.g., a 25 percent ownership interest) rather than 100 percent of the business. In these cases, analysts may estimate discounts for lack of control and marketability. Simply put, a 25 percent interest in a business worth $1 million may be worth less than $250,000 because the owner of a 25 percent interest may be limited in their ability to take any action they choose (i.e., their interest lacks control) and sell their interest (i.e., their interest lacks marketability). When appropriate, analysts discount the indicated company values for lack of control and marketability.

Conclusion

Business valuations are fundamentally similar to real estate appraisals. Both use three approaches to value that are applied in a parallel manner. By educating themselves on the subtle differences between these two crafts, real estate appraisers will be able to better serve their clients.

About the Author

Seth Webber is the head of BerryDunn’s valuation services group, where he helps business owners understand what their business is worth. Seth can be reached via email at swebber@berrydunn.com or by phone at (207) 541-2297. Casey Karlsen is a manager in BerryDunn’s valuation services group. Casey can be reached via email at ckarlsen@berrydunn.com or by phone at (207) 842-8053.

OREP Insurance Services, LLC. Calif. License #0K99465